Part of a series of data sets collected in the Irish Sea, off North Wales, under the Civil Hydrography Programme (CHP) has given us a fantastic insight into the geological past of the UK.

The CHP is a long-running data collection programme undertaking systematic surveys of the UK’s coastal waters. Administered by the Maritime and Coastguard Agency (MCA), experts at the UKHO provide technical oversight and data validation. This data is used to update the nation’s nautical charts and publications to ensure they remain current, safe and fit for purpose.

Collecting high-quality data provides information that can be used for much more than Safety of Life at Sea – as UKHO Geospatial Information Specialist Laurence Dyke discovered when analysing the data sets collected off North Wales in the Irish Sea.

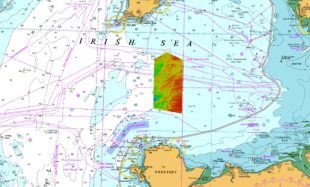

Location of HI1706 overlaid on Chart 1121: Irish Sea with Saint George’s Channel and North Channel. Image credit: The MCA and the UKHO (2022).

British-Irish Ice Sheet

Laurence and the Scientific Analysis Group at the UKHO discovered a series of remarkably well-preserved landforms left by huge glaciers during the last glaciation. Global cooling at the start of the last glaciation allowed embryonic glaciers to form over high ground across Great Britain and Ireland. As conditions cooled, glaciers continued to grow, coalescing and flowing radially outwards, away from the mountains and across the lowlands and continental shelf to form the British-Irish Ice Sheet. Around 27,000 years ago, the ice sheet covered an area of 840,00 km2 and contained enough ice to raise global sea levels by 1.8 m(1).

The present-day Greenland Ice Sheet with protruding nunataks. An analogue for the British-Irish Ice Sheet 27,000 years ago. Image credit: Laurence Dyke (2015).

The British-Irish Ice Sheet stretched from the Isles of Scilly to the Shetland Islands, and flowed out to the continental shelf edge along its entire western flank(2). In the east, the British-Irish Ice Sheet was confluent with the vast Fennoscandian Ice Sheet, with glaciers flowing from this saddle down the North Sea and reaching the coast of Norfolk(2).

The ice sheet inundated Great Britain and Ireland with glacial ice several kilometres thick and was characterised by dendritic, or tree-like, ice flow(3). Several very large glaciers, known as ice streams, drained ice from the mountainous areas down to the ocean, calving icebergs into the Atlantic. These huge marine-terminating outlet glaciers flowed at speeds of several kilometres a year, analogous to the largest glaciers in present-day Greenland and Antarctica(3).

The evolution of the British-Irish Ice Sheet through the last glaciation. Image credit: BRITICE-CHRONO Project/Chris Clark (2022).

The largest ice stream flowed southwards through the Irish Sea, draining more than 17% of the ice sheet(4) including ice from source areas in the Galloway Hills, the Lake District, Snowdonia, the Cambrian Mountains, and the Wicklow Mountains. Fast and erosive ice flowed through the Irish Sea basin and into the Celtic Sea, extending to the shelf edge south of 49°N, roughly level with northern Brittany(5).

Subglacial landforms show extensive field of drumlins

The recent hydrographic survey data collected from the seabed in the centre of the Irish Sea shows a remarkably well-preserved suite of subglacial landforms; features formed by the bed of the glacier as it flowed over sediments and bedrock in the area.

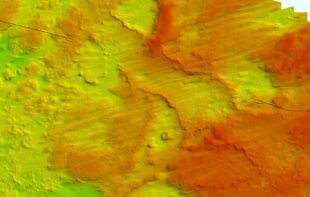

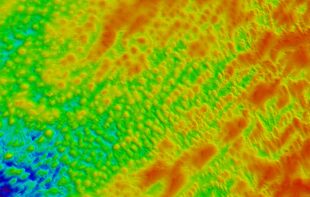

Extensive drumlin field in the centre of the Irish Sea. Large erratic boulders and eroded bedrock ridges are also visible in the data. The former direction of ice flow was from northeast to southwest. Image credit: UKHO (2022).

Arguably the most impressive subglacial landform in the newly surveyed area is the extensive field of drumlins. These mounds of glacial sediment can be tens of metres high and hundreds of metres long, and are generally elongated in the direction of ice flow. In profile, drumlins often have a blunt upstream or ‘stoss’ side, and a tapered downstream or ‘lee’ side. Drumlins only form beneath thick, fast-flowing ice. Their presence indicates that the Irish Sea Ice Stream was over 1000 m thick here and was flowing at speeds of several kilometres a year when these features were created.

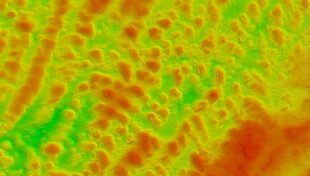

Drumlins and ribbed moraines in the centre of the Irish Sea. The transition between the two landforms is subtle; ribbed moraines are well-developed in the shallower areas in the east, while drumlins dominate the deeper western areas. Image credit: UKHO (2022).

A little further to the south, closer to land, there is a gradual transition from drumlins to linear ridges of sediment that are aligned perpendicular to the ice flow direction. These ridges are ribbed moraines(4), also known as ‘Rogen moraines’ after the spectacular example found around Lake Rogen in Sweden. The origin of both drumlins and ribbed moraines have been hotly debated, but it is now generally accepted that these features are part of a continuum of subglacial landforms, formed by pattern-forming instabilities as glacial ice, and deformable layers of underlying sediment, behave like fluids during glacier flow.

Aerial photo of well-preserved ribbed moraines (Rogen moraines), Lake Rogen, Sweden. Image credit: Laurence Dyke (2019).

Ice retreated from the area around 20,000 years ago

There are also numerous moraines visible throughout the survey area. The most prominent, and best preserved, are in the north of the survey area. These are likely recessional moraines, marking still-stands or brief pauses of the glacier front during general retreat at the end of the last ice age. They indicate that as ice retreated from this area around 20,000 years ago, it was still grounded, or in contact with the seabed, and the glacier system had not thinned enough to float.

The sinuous ridges in the centre of the image are likely recessional moraines. Note the submarine cable in the east and west of the image and lineations of streamlined bedrock showing the direction of previous former flow. Image credit: UKHO (2022).

There are a myriad of other interesting features to be found within the data from this new survey, including glacial erratic boulders, mega-scale glacial lineations, flutes, and even a possible large esker system. Glacial features across Great Britain and Ireland have been extensively mapped over the past 150 years, and the history of the British-Irish Ice Sheet is better understood than anywhere else on Earth. However, there are still plenty of areas for further research, and this new data may help resolve some of them. In time, surveys like this will be fully analysed by glacial geomorphologists and added to maps of ice sheet landforms.

It is possible to explore the latest glacial maps of Great Britain and Ireland and even to download the data. These are available through the BRITICE-CHRONO project(3)